The (r)evolution continues for commercial lending

- 8 March 2024

Brokers are set to benefit as changes in commercial markets accelerate – where the money goes, the tools used to broker the deal, and who provides the loan.

COMMERCIAL LENDING in Australia is evolving in terms of both who is doing the lending and what the lending is for – trends that look set to become long-term economic drivers for years to come. These changes show the market is maturing and more able to respond to short-term negatives, while also being nimble enough to grow when opportunity beckons.

The typical lender profile has undergone significant change over the last 10 years, which has seen traditional banks retreat and non-banks take a larger share.

A recent report by Foresight Analytics shows that the market for Australian commercial real estate debt now stands at $447 billion, with $74 billion – or a 16% share – attributed to non-bank lenders, up from just over 10% in 2020. Non-bank lenders are now key players in the commercial space, while traditional banks have increasingly retreated to less risky residential lending.

“Traditional banks tend to avoid complex commercial deals, preferring the more straightforward loan applications, whereas we embrace complexity,” says Paul Bakker, national manager for sales and strategic partnership at Better Choice Home Loans.

While part of the reason for this can be attributed to a higher risk aversion among banks, non-banks have also helped drive the market with their more flexible policies and willingness to consider factors in a lending proposition that a bank might not.

“Just some of the factors we consider that traditional banks may not touch are the wide range of securities we allow, our commitment to no annual reviews or revaluations, our Easy SMSF refinance process, our reduced documentation requirements and unlimited cash-out solution,” says Bakker.

Finding workarounds for unusual problems is par for the course for non-banks.

“Even when customers have complex scenarios, we make it easy to find suitable solutions to fit their needs,” says Matthew Heinnen, group manager for commercial at non-bank Liberty.

“For example, we can combine line-of-credit facilities and even short-term business loans to unlock superior commercial solutions for clients across a wide range of credit profiles.”

Commercial lending moves from office to industrial

Another recent change is where the money is being invested.

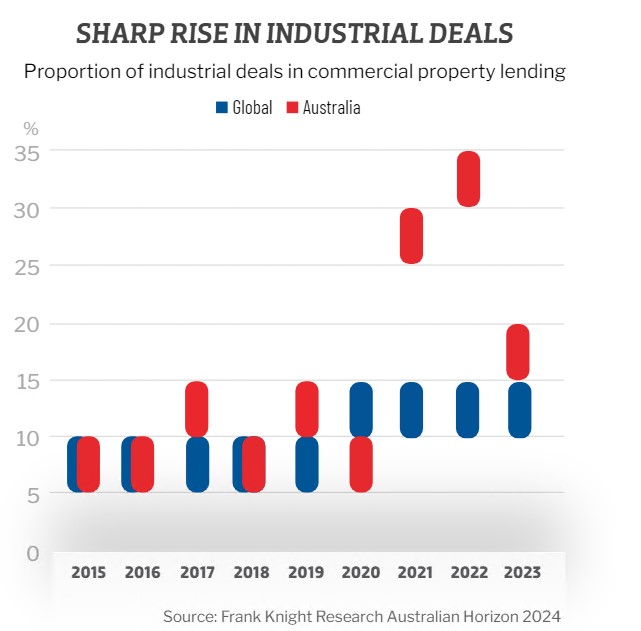

Compared to before the pandemic, commercial lending is now much more focused on industrial property at the expense of office and retail. According to Frank Knight Research, between 2008 and end 2019 some 43% of total Australian investment volumes were in the office sector, 22% in retail and only 13% in industrial – broadly in line with commercial lending trends in other countries.

However, from 2020 onwards the proportion of industrial deals spiked as companies adopted strategies to cater to the growth of online shopping or mitigate supply chain woes by building more warehouses to hold stock locally. Property developments targeting an ageing population have also increased. As the proportion of industrial investments has risen, lending for office and retail in the post-pandemic environment has fallen.

This is partly due to markets grappling with changes in local working styles and living habits, but also due to deeper trends around having a backstop to offset the increasing fragility of global trade. Think the war in Ukraine, Houthi missiles, supersized ships jamming up the Suez Canal, or reduced traffic in the Panama Canal due to climate change-induced drought.

While onshoring is likely to continue, non-banks are sometimes better positioned to deal with uncertainties around supply chain disruptions than more risk-averse traditional lenders.

“For those more susceptible to global disruptions, this can quickly result in decreased revenue and cash flow challenges for businesses, meaning lenders become more cautious about extending credit to businesses with such wild fluctuations,” Bakker explains.

But non-banks like Better Choice are generally more agile. “We can make quick policy changes to adapt to the current situation, especially in those instances where an unforeseen event arises that causes interruptions to the commercial lending space,” says Bakker.

Australia really is the lucky country

Other parts of the world didn’t follow Australia’s exodus from office and retail property lending to the same degree, and some of those chickens appear to be coming home to roost in 2024 in markets such as the US, almost as a redux of the US banking crisis of early 2023 (remember SVB?).

Just as the US banking crisis last year didn’t have much impact in Australia beyond generating headlines, the change in the Australian commercial playbook towards a higher industrial weighting likely insulates it from any contagion stemming from shaky commercial markets abroad.

The Reserve Bank of Australia noted as much in its latest Financial Stability Review, saying that while conditions are challenging for lower-grade offices, industrial properties are continuing to perform strongly due to increased demand for distribution and warehouse facilities. Non-performing loans for commercial property notched up slightly in 2023 but remain at only a fraction of the levels seen in the aftermath of the GFC.

Australian markets are hoping any turbulence in commercial markets afar will stay there.

“Sentiment is inconsistent but with some signs of positivity despite stress in overseas commercial real estate markets,” says chief revenue officer Brian Steele at LBH Partners, a technology adviser for digitalisation in commercial lending.

In US markets, office vacancy rates hit an all-time high in the fourth quarter of 2023, beating a record that had stood for around 30 years. Compare this with industrial vacancy rates in places such as Sydney, which hit record lows in 2023 and continue to hover at similar levels. Annual rental growth remains high, with Sydney and Brisbane at 30% and 20% year-on-year respectively.

With available supply still set to remain tight for the foreseeable future, the industrial market is expected to continue to attract investment on the back of strong economic and population growth fundamentals and ongoing rental growth expectations. What’s not to like?

A tough economy as both a headwind and a tailwind

To be sure, the pandemic took the wind out of the sails of a number of economic sectors.

“[It] caused disruptions to various industries, particularly those reliant on travel, hospitality and retail. Many businesses faced revenue declines, cash flow challenges and uncertainty about the future, leading to reduced demand for commercial loans,” says Bakker.

Much of the disruption is only just beginning to settle down. But even as a tough economy adds more caution to the lending appetites of traditional banks in the commercial market, this may not necessarily be the case at non-banks across the street.

“Times like these allow a lender like Liberty to look at a range of non-traditional lending criteria to achieve an innovative outcome,” says Heinnen.

Non-banks have more levers they can pull to help investors with their latest projects such as warehouses or medical centres, and brokers are often impressed at what they can seemingly pull out of a hat.

“We are quite adept at finding ways to help more borrowers when they need it most,” says Heinnen. “Looking beyond the credit score and taking in the full picture helps us support commercial borrowers through whatever changes might occur.”

In fact, the recent commercial market stress in the US might end up helping non-banks gain further market share by forcing their mainstream competitors to reassess their risk profiles.

“With the overseas lending environment in commercial property having tightened, particularly in the US, we are likely to see risk settings in our market remaining tight in the near future,” says Steele.

This is part of a far more long-term dynamic that will see the services of non-banks needed in economies both good and bad.

“In times when interest rates are low and the general commercial activity from investors and developers is greater, the banks tend to be more liberal with their lending, yet non-bank lenders are still needed because of the sheer appetite of the borrowing market,” says Dean Koutsoumidis, managing director and founder of Equity-One.

“Interestingly, though, when interest rates increase and banks’ credit policies tighten somewhat, we find the borrowing demand continues for non-banks because whilst there may be a contraction in commercial activity in the market, there is also a contraction in the availability of bank credit.”

With around 30 years’ experience in the business, Koutsoumidis has seen these patterns play out during the 1990s, the GFC, the COVID pandemic and everything in between.

A continuing need for cash among businesses

The 2024 market will be no different in that regard. “As the economic climate changes, different factors may be at play, but the underlying need for non-bank funding doesn’t change,” Koutsoumidis says.

Higher interest rates will continue to keep consumers pessimistic and tight-fisted with spending, grinding the patience of small to medium-sized enterprises in particular.

The January read of the Westpac-MI Consumer Sentiment Index was in the bottom 7% of all observations since the survey was first run in the mid-1970s. SMEs are increasingly seeking more cash for working capital – the latest Fifth Quadrant SME Sentiment Tracker shows that a high 64% need funding over the next three months for this purpose.

This dovetails with a record-low average value of B2B invoices in the latest CreditorWatch Business Risk Index, indicating that trading conditions may become even tougher for businesses, with confidence remaining subdued and input costs elevated.

In such an environment, borrowers in commercial markets can have the rugs pulled from under their feet by their regular banks.

“A typical transaction would be where an applicant has purchased a commercial property and settlement is looming fast, but the bank hasn’t committed with a yes or no. In these cases, many borrowers are caught by surprise because they would have had a good previous history with their banker,” Koutsoumidis says.

The borrower’s problem is normally short-term, so non-bank lenders like Equity-One provide loans designed to be repaid at any time with no break costs – knowing that a customer’s main bank will often step in and take over again down the track.

“This approach to lending has not changed since the ’90s, in that brokers still need an alternative to when their major can’t come to the party or can’t [come] in time.”

Demand from SMEs for business loans shot up towards the end of 2023, according to RBA data, against a striking fall in lending to large businesses on a same-month comparative basis. Major banks becoming more risk averse and non-banks taking up the slack with SMEs is likely one of the reasons.

A differently shaped economy

Various sectors are still adapting to post-pandemic realities, and this will continue to play out even when rates eventually drop.

Bakker is picking e-commerce and retail to continue down the path it was forced onto in 2020.

“The COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated the shift towards online shopping, and businesses are increasingly investing in digital platforms and logistics infrastructure to cater to changing consumer preferences. Traditional brick-and-mortar retailers will need to adapt and find innovative ways to integrate their physical stores with online operations to stay competitive.”

Another sector to watch is advanced manufacturing.

“Australia is focusing on developing advanced manufacturing capabilities to enhance competitiveness and reduce reliance on imports. The government’s Modern Manufacturing Strategy aims to promote growth in areas such as medical products, clean energy, defence, space, and food and beverages.”

SMEs in general are also in for more change.

Steele says, “SME businesses are a segment of the market that’s likely to experience significant transformation, particularly businesses of more than 10 staff where there are structural complexities like multiple directors and entities.”

This is an area that large banks have historically shied away from due to the lack of profitability of using sophisticated credit and loan management processes for a typically small loan size. But this is starting to change on the back of new technology, which could see more competition among traditional banks and smaller non-banks for the SME market.

“Technology is helping lenders handle this sophistication at a dramatically lower cost [which] is driving transformational innovation,” Steele says.

Technology to allow more brokers to enter commercial markets

The COVID years saw the number of mortgage brokers also writing commercial loans grow quickly. While MFAA data for the latest six-month reporting period showed a 4.2% decline in numbers, this was the first drop since 2019, and the figure is still more than 30% higher than in March 2020.

While commercial has a reputation for being more complex than residential lending, non-banks have played a key role in making commercial easier to understand.

“We have found our commitment to making commercial lending simpler is what sets us apart from our competitors,” Bakker says.

“Starting with simplified documentation, our alt-doc loans typically require fewer supporting documents than our competitors, making the application process quicker and more streamlined. This is particularly beneficial for self-employed individuals or small business owners who may not have the same level of documentation as salaried individuals.”

Technology, too, is lowering the barriers for those new to commercial, which will encourage more brokers to join the fray.

“Technology is playing a big part in driving this growth as lenders and aggregators invest in intuitive loan application workflows which are easier for brokers and borrowers to experience. It’s early in the journey, but you are definitely seeing broker portal, fact-find, matchmaker and lodgement tools similar to residential mortgages being launched in the commercial space,” Steele says.

Just as many lenders have substantially invested in new tech tools for residential lending processes on the back of the pandemic, these same tools are being deployed for commercial lending.

“Lenders are learning from their residential mortgage experience that digitising the application process for brokers improves conversion and minimises rework for the lender,” Steele says. “This in turn drives cost reduction, improves efficiency and optimises data quality.”

Introducing such digital processes to the commercial side used to be too expensive, but this has changed with the adoption of generative AI and robotic process automation. A recent report from Accenture showed that generative AI will transform work across many industries, but of the 20 industries included, the highest potential for change was in banking.

“The way in which we all do business is constantly evolving in this digital era, and challenges for lenders to deliver for their brokers and borrowers remains front of mind for participants. The evolution of AI will undoubtedly, too, play a major role in how services are delivered to borrowers and brokers in ways that we perhaps can’t quite fathom… yet,” Koutsoumidis says.

But this also provides an environment for opportunity.

Commercial lending is undergoing a radical transformation – in terms of where the money goes, the tools that are used to broker the deal, and who provides the loan when. With Foresight Analytics predicting that the non-bank share of commercial lending could account for almost a quarter of the commercial real estate debt market by 2028, there is no doubt that the evolution will continue at pace.

“We feel that the needs for alternative lending will remain strong, and our Australian market is continuing to mature,” Koutsoumidis says.

View the original article here